Goose Lake Prairie Partners, Inc.

Volunteers at Goose Lake Prairie State Natural Area

5010 N. Jugtown Road off Pine Bluff Road, Morris, IL 60450

Site Index:

Park Programs

Fundraisers

Prairie Partner Activities

Cabin Festival

Nature Photo Contest

Prairie Day

Holiday Party

Gift Shop

Hiking Trails

Nature Study

Fishing & Hunting

Donors & Donations

Tallgrass Journal

Take only Memories. Leave only Footprints. Thank You

Very Kindly.

|

The Tallgrass Journal has temporaily

discontinued publication. Tallgrass Journal - Download the last Tall Grass Journal Issue. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A very limited number of copies are available at the

visitors center. We

publish quarterly.

Archives:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Encountering The Cragg

Cabin: Preservation And A Sense Of

The Past

by Hal Hassen, IDNR Archaeologist

When

we enter our homes from the outside we usually do not think of the past.

We are surrounded by modern technology and conveniences.

Cross the threshold of Lincoln’s home and we think not of the present but

of the past.

The Cragg

cabin located at Goose Lake Prairie State Natural Area similarly evokes thoughts

of the past.

The Cragg cabin

was originally constructed in the 1830’s and stood for 100 years before it was

moved and underwent extensive repairs.

Over the years the cabin has undergone additional rebuilding phases and

was eventually moved to its current location at the state park.

Does the cabin resemble the original Cragg cabin in all its details

constructed over 170 years ago?

It

probably does not.

However, is an

accurate representation of the physical qualities of the cabin most important or

is the message conveyed by the cabin more significant.

For me, the past is not a place; it is a state of mind.

Absent a time machine, we can never really live in the past.

We are, however, interested in the past.

The reasons are numerous but for many of us there is interest in

comparing what life was like in the past to how we live today.

This includes technology and social customs and beliefs.

Lincoln’s home in Springfield sits on its original lot and is surrounded

by several houses that would have been present when the Lincolns lived at their

house.

However, when visitors stand

in the street outside they stand on a well groomed gravel road and easily see

many of the large commercial buildings that make up the surrounding

neighborhood.

So while much of

the original context and fabric of the buildings remain intact, there have still

been many changes from how the

neighborhood and the house looked in the mid-1800s.

Historic rehabilitation and reconstruction is tricky.

One always tries to maintain as much of the original look as possible.

Unfortunately many factors can make it difficult to adhere to 100 percent

historical accuracy.

When the Cragg cabin was again rebuilt and moved to its current location, the

participants meant to create something that would have provided the visitor with

a sense of the past.

Despite some

problems with its appearances, the Cragg cabin still conveys a strong sense of

the past for the visitor.

Walking

into the Cragg cabin or even seeing it from afar, the visitor is immediately

presented with thoughts about the past.

Comparisons are made between old and new technology.

Comforts we take for granted are even more relished when faced with the

harsher conditions which probably existed based on the timber framing

illustrated in the Cragg cabin.

As the archaeologist for the Illinois Department of Natural Resources it is my

responsibility to ensure that the Department protects it’s archaeological sites

and significant standing structures so they are preserved for the future.

Once protected, a structure can be interpreted for the public.

Good interpretation will then enhance visitor appreciation for the

resource.

A well informed public

with appreciation for historic resources will inevitability lead to increase

protection and broader public support for historic preservation.

Public involvement in moving and reconstructing the

Cragg cabin is particularly rewarding when younger people are involved.

The participants take with them an appreciation for historic

preservation, while presenting the visitor a window into the past.

The region surrounding the Goose Lake Prairie State Natural Area was

settled later than other areas in Illinois.

Nonetheless the conditions faced by those first settlers were harsh and

difficult.

Building materials were

gleaned from the natural environment and houses were built using skills and

techniques less common today.

There is no question that a visitor to the Cragg cabin will come away

with some sense that life was different 170 years ago.

In the end I think that is what is most important.

Reflecting upon the past and what it means can be triggered by old photographs,

stories, or the physical presence of old buildings.

The Cragg cabin speaks to us about early settlers and

lost technologies.

See Our history page for more information on the Cragg Cabin.

2010-2011 Hunting Season, a review by CPO Dave Wollgast

The deer hunting season at Goose Lake Prairie and the new Morris

Wetlands was a great success this year!

Of the 678 registered archery hunters for both sites there was a

total of 20 bucks and 29 does killed on the Morris Wetlands alone

according to the hunter fact sheets.

We do not have the results for archery hunting at Goose Lake

Prairie as of yet, but the numbers seemed to be good for the amount of

guys who hunted it. The

firearm season was exceptionally successful.

Of the 822 hunters who hunted during the 5 firearm seasons we had

18 bucks and 26 does shot on the Morris Wetlands and 25 bucks and 25

does shot at Goose Lake Prairie/Heidecke Lake.

The program was not only a success for the hunters, but the

biologists and forester as well.

The large numbers harvested will greatly aid in controlling the

overabundant population which was devastating the trees the Illinois

Department of Transportation had planted to help mitigate the Morris

Wetlands.

We had some enforcement issues at the Morris Wetlands this season.

Some guys were forgetting to sign in and out as they went into

the property. Most of these

guys have been dealt with and now understand the importance a little

more. The records obtained

from the sign in and out and hunter harvest information on the check

sheet is not only a legal requirement, but helps our biologists

determine what the program needs or is in excess of.

The less compliance we receive on the sheets the more problems we

have in maintaining the property and allowing it to stay open to public

hunting. We also had some

hunters who were not removing their tree stands at the end of their

hunts. It is an

inconvenience to carry your stand all the way in and set it up and take

it down for each hunt,

however, by doing so you are allowing for one of the other 678

registered hunters to also use the area.

The waterfowl hunting at Heidecke Lake was mediocre this year.

Due to an early onset of cold weather that held fast the lake

remained closed for a good portion of the season due to the ice.

Of the 35 days hunted the following numbers were harvested.

Canada Geese- 13, Mallards- 290, Black

Ducks- 12, Blue Winged Teal- 2, Green Winged Teal- 7, Hooded Merganser-

11, Common Merganser- 9, Red Breasted Merganser- 1, Goldeneye- 125,

Ruddy- 4, Scaup- 19, Bufflehead- 20,

Shovelers- 28, Ring-necked- 29, Redhead- 9, Canvasback- 3,

Gadwall- 29, Pintail- 2, Wigeon- 2, and Other- 1.

Overall it was a good, safe hunting season at Goose Lake Prairie,

Heidecke Lake and the Morris Wetlands.

We hope to have another successful and safe season in 2011-2012.

David Wollgast

Conservation Police Officer

Goose Lake Prairie State Natural Area,

Heidecke State Fish and Wildlife Area, and Morris Wetlands

Posted August 9, 2011.

This article appeared in the Winter (January) 2011

issue on page 8.

Fire on the Prairie

Fire is an essential

component of the tallgrass prairie; it keeps invading trees and shrubs at bay,

controls non-native species, makes

nutrients more readily available to prairie plants, and promotes diversity in

both the prairie plant community and wildlife habitat structure.

Fire was a natural component of the pre-settlement landscape of Illinois,

and Goose Lake Prairie is almost entirely dependent upon it.

Without fire, Goose Lake Prairie would become an impenetrable woody

thicket in a matter of a few decades.

Pulling off a controlled burn at Goose Lake Prairie is no small feat.

This site is one of the trickiest in the state, due to its sheer size and

fuel type (burn managers refer to a site’s combustible vegetation as “fuel”).

Tallgrass prairie fuels can easily produce flame heights of 40 feet and

taller.

An experienced crew of

certified burn managers is required to safely conduct a prescribed fire at Goose

Lake Prairie.

The fire boss assembles a burn crew from the region, usually comprised of 8-15

individuals (depending on the complexity of the burn), all equipped with

fire-resistant Nomex suits and wildland fire-fighting equipment.

There are a minimum of 4 all-terrain vehicles, each rigged with 50

gallons of water, 200 feet of hose, and a high-pressure pump.

Hand tools such as drip torches,

rakes, flappers, and 5-gallon backpack sprayers are also required on each

fire.

A back-up water supply of

several hundreds of gallons is also on site.

Goose Lake Prairie is divided into multiple burn units easily denoted by the

mown strips.

Some units are only 40

acres, whereas other units may be over 600 acres in size.

Most burn managers do not burn 100% of the natural area in one season;

there should always be unburned vegetation to serve as a refuge for insects and

other wildlife.

It is also

desirable to have diversity in the habitat structure of a large grassland to

accommodate the variety of nesting grassland birds.

Some birds, like the Henslow’s Sparrow, prefer a thick accumulation of

grasses, and other birds such as the Grasshopper Sparrow, are more abundant

after a recent burn.

The site’s

biologists rotate burn units, and usually try to burn a couple units each year

at larger sites, as

weather

permits.

The burn unit is defined by its firebreaks, which can be natural features or

man-made.

At Goose Lake Prairie,

the burn units are designed using mowed trails, roads, and bodies of water.

The burn crew begins at the downwind side of the burn unit by lighting

the fuel (dried prairie vegetation) at the edge of the unit immediately adjacent

to a mowed trail or road.

The fire

spreads in all directions, but at varying rates, depending on wind speed and

direction.

The rapidly spreading

downwind side of the fire is extinguished by spraying water and snuffing it out

with hand tools, or simply when the fire reaches a firebreak with no fuels, like

a road or open water.

The upwind

side of the fire is allowed to slowly creep into the wind, towards the middle of

the burn unit (know as a “back-fire”).

The fire boss evaluates the behavior of the fire while it is still small

and easy to extinguish.

If the fire

is behaving as expected under the weather conditions and fuel type, the crew

splits into two teams, heading in opposite directions.

Each team uses drip torches to light along the firebreak, working with

the wind and extinguishing the downwind flames along the firebreak.

The fire within the unit is allowed to continue creeping upwind so

the firebreak is widened by creating a “black line” of burned fuel.

This is the most critical and time consuming element of conducting a

controlled burn.

The fire teams are in constant communication with each other while lighting the

back-fire, and regularly monitor the weather.

Temperature, humidity, wind speed, and wind direction can vary throughout

the day and greatly influence fire behavior.

The teams continue lighting along the edges of the fire unit,

almost

circling the unit, until it is time to make the turn where the wind will carry

the head-fire.

Both teams hold

steady while the fire boss evaluates the width of the black line.

As a general rule of thumb, the black line at the downwind side of the

burn unit should be 3 times as wide as the tallest expected flame height.

If there is plenty of black line, one or both of the teams are given the

go-ahead to completely circle the unit and light the head-fire.

As the two teams meet up again, flames roll over the prairie, consuming

nearly everything in their path.

The fire extinguishes itself when the head-fire is pushed by the wind into the

back-fire, where there is no more fuel left to burn.

This

past fall was an exceptional season for conducting prescribed fire at Goose Lake

Prairie (among other sites within the region).

The weather was unusually warm and dry, with favorable winds keeping

smoke off Pine Bluff Road.

Two

burns were conducted; both immediately north of Pine Bluff Road, and on either

side of Jugtown Road.

The western

unit went exactly as planned.

The

eastern unit however, kept the burn crew working into the night.

While back-burning and widening out the black line through a part of the east

unit which is dominated by the non-native common reed (Phragmites

australis),

the fire had jumped the line.

Phragmites

is one of the most invasive plant species in our wetlands, and it can grow up to

10 feet tall.

When dense stands of

it ignite, flame heights can easily get up to 50 feet.

During the back-burning portion of this prescribed fire, the super-heated

air column above the burning

Phragmites

pushed a lit ember up and outside the burn unit.

The burn crew quickly implemented the back-up plan which was discussed before

the fire was even lit.

They would

allow any escaped fire to burn until it reached the open water of the wetlands

located downwind.

The wind was

pushing the escaped head-fire straight for the wetlands, and fire crews had to

contain only the flanking-fire, with flame heights of about 3-6 feet.

When the controllable flanking-fire met up with the open water wetlands,

the escaped fire would be extinguished.

However, the fire boss decided additional resources were needed and

contacted two local fire departments.

Coal City and Morris Fire Departments were invaluable in providing the

IDNR fire crew with extra water used in controlling the escaped fire, staging

additional wildfire equipment, and keeping travel on Pine Bluff Road safe (some

drivers have a tendency to watch a fire instead of the road!).

After gaining control of the escaped fire, the burn crew needed to complete the

prescribed fire within the rest of the original unit.

The back-burning and widening the black line still needed to be

completed.

This slow process was

made even slower due to cooling temperatures and rising humidity.

The head-fire was eventually lit around 7 pm, and final mop-up wasn’t

completed until after midnight.

A fire at Goose Lake Prairie is always an impressive sight.

Witnessing Goose Lake Prairie ablaze and glowing into the night was even

more of an awe-inspiring spectacle.

This

is not the first time Kim Roman has written for the Tallgrass Journal.

We welcome her articles.

Kim

is employed by the

Illinois Nature Preserves Commission.

Posted April 15, 2011from the Spring 2011 Tallgrass Journal.

Switchgrass:

Native Prairie Species

Switchgrass:

Native Prairie Species

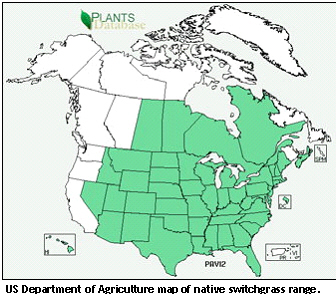

Panicum virgatum

L., or switchgrass, is a warm-season perennial grass species native to much of

North America.

Historically, it was

a major component of tallgrass prairie ecosystems, although wild populations

have declined in recent decades due to the loss of most of our native prairie

range.

Switchgrass can still be

found in native prairie remnants, which are distinguished from other prairie

systems by the lack of human disturbance or length of time since disturbance,

and are presumed to contain the descendents of the once vast tallgrass

communities.

Over the last several

decades, however, switchgrass has been selectively bred by the USDA and others

for different purposes, most recently for use as a biofuel, and mass plantings

are seemingly imminent in several central and Midwestern states. The potential

impact of biofuel cultivars on wild relatives is, as yet, unknown.

Switchgrass is naturally a range grass and has been fed upon by ruminants for

centuries, but it became a focus of study for use as a forage crop by scientists

in the early 1970’s.

Backed by the

USDA, agronomists selected individual switchgrass plants that possessed

desirable traits, such as increased biomass, high digestibility, or better

winter survival, perhaps reducing genetic variability and increasing

homogeneity, compared to the wild forbears.

Over the years, the USDA has released several switchgrass cultivars, each

selected and/or bred for specific traits.

In the late 1980’s, switchgrass became one of several species of interest as a

potential biofuel crop (biofuels, whether burned or converted to ethanol, are an attractive alternative to conventional

fossil fuels because they are renewable and have the potential to be more

economical and environmentally friendly than conventional fuels).

By the early 1990’s, researchers at the USDA and other groups, like

Ceres, Inc., had determined that switchgrass had great potential as a biofuel

and their research efforts, funded in large part by the Department of Energy,

continue to look for ways to make ethanol conversion efficient and economical.

Traits that were attractive in forage switchgrass are now being selected

to a greater extent in biofuel switchgrass, which could further reduce genetic

variability of the cultivar.

Added

to this is the fact that a few research groups are attempting to genetically

modify switchgrass by inserting foreign genes, or “transgenes,” into the plant’s

genome in order to increase the speed with which switchgrass becomes biofuel-ready.

Genetic modification of switchgrass is not currently practiced by the

USDA, who oversees the commercial release of cultivars.

However, non-transgenic biofuel switchgrass appears to be on the verge of

widespread plantings across several U.S. states.

burned or converted to ethanol, are an attractive alternative to conventional

fossil fuels because they are renewable and have the potential to be more

economical and environmentally friendly than conventional fuels).

By the early 1990’s, researchers at the USDA and other groups, like

Ceres, Inc., had determined that switchgrass had great potential as a biofuel

and their research efforts, funded in large part by the Department of Energy,

continue to look for ways to make ethanol conversion efficient and economical.

Traits that were attractive in forage switchgrass are now being selected

to a greater extent in biofuel switchgrass, which could further reduce genetic

variability of the cultivar.

Added

to this is the fact that a few research groups are attempting to genetically

modify switchgrass by inserting foreign genes, or “transgenes,” into the plant’s

genome in order to increase the speed with which switchgrass becomes biofuel-ready.

Genetic modification of switchgrass is not currently practiced by the

USDA, who oversees the commercial release of cultivars.

However, non-transgenic biofuel switchgrass appears to be on the verge of

widespread plantings across several U.S. states.

While

the creation of a cleaner, more economical fuel is by no means objectionable

per se,

there is a lack of empirical scientific research about general switchgrass

ecology, and virtually nothing is known about the potential impact of

switchgrass cultivars on wild relatives.

Some researchers and conservation groups have expressed concern that

cultivars could escape cultivation and become a weedy invader or cross with wild

relatives, producing hybrids that could dilute the native gene pool.

Others believe that since forage cultivars were derived from wild

ancestors and breeding cycles take years to complete, cultivars are not that far

removed genetically from wild counterparts.

However, there are very few scientific studies that have addressed these

questions directly.

While

the creation of a cleaner, more economical fuel is by no means objectionable

per se,

there is a lack of empirical scientific research about general switchgrass

ecology, and virtually nothing is known about the potential impact of

switchgrass cultivars on wild relatives.

Some researchers and conservation groups have expressed concern that

cultivars could escape cultivation and become a weedy invader or cross with wild

relatives, producing hybrids that could dilute the native gene pool.

Others believe that since forage cultivars were derived from wild

ancestors and breeding cycles take years to complete, cultivars are not that far

removed genetically from wild counterparts.

However, there are very few scientific studies that have addressed these

questions directly.

Some ecologists have risen to the challenge and are trying to keep pace with

agronomic research and development by addressing the more urgent questions

related to switchgrass ecology.

Researchers at universities such as Ohio State and Iowa State, for example, are

collaborating to tackle some of these pressing questions.

Hopefully soon, we will have good, empirical data that will shed light on

any potential risks associated with biofuel cultivars, so we can make informed

decisions about whether and where to plant biofuel switchgrass.

Several remnant prairie patches exist in and around Grundy County, Illinois, and wild switchgrass populations can be found at Goose Lake Prairie, Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie, Des Plaines Conservation Area, Grant Creek Nature Preserve, and Hitt’s Siding Nature Preserve. While the switchgrass populations located in these prairie remnants are not large, they are nevertheless an important component of the remnant prairie community. Since we don’t really know what, if anything, will happen to wild populations when biofuel types are introduced, new research is vital to our increased understanding of this species.

Amy L. Campbell, M.S. is a Ph.D. student studying plant ecology with Dr. Allison Snow at The Ohio State University in Columbus, Ohio. Amy has three main goals: to determine the potential for gene flow between cultivated and wild switchgrass populations, to investigate genetic similarity between the two groups, and to examine fitness-related traits as a measure of the potential invasiveness of cultivars in relation to wild counterparts. It is important to Amy’s work that she sample switchgrass individuals from truly wild populations (as opposed to restored areas).

Luckily, Goose Lake State Park has a few true remnant prairie patches, which are

becoming increasingly rare and, thus, harder to find.

In 2009 and 2010, with the help of prairie specialist Art Rohr, Amy

visited Goose Lake Prairie and collected leaf tissue and seeds from switchgrass

individuals growing in the remnant prairie patches.

She will use these samples in her research, and hopefully the information

Amy discovers can be used as an important jumping-off point for future

ecological studies about biofuel switchgrass.

(Excerpt from the January (Winter) Tallgrass Journal, 2011.)

The

Submitted by Chris Rollins

Our special article on Illinois

Prairie History this month was written by Christopher Rollins.

Chris is in his

third year as Regional

Land Manager, IDNR Region 2 and frequents Goose Lake Prairie SNA very

often. Chris holds a double major in Animal Science; and Political Science

and a Bachelor of Arts -Board of Governors’ Degree from Western Illinois

University.

Sunmer 2009 Issue of the Tallgrass Journal.

Historically, we know that the Illinois River was important among Native

Americans and early French traders as the principal water route connecting the

Great Lakes with the Mississippi. The colonial settlements along the river

formed the heart of the area known as the Illinois Country. After the

construction of the Illinois and Michigan Canal and the Hennepin Canal in the

19th century, the river's role as link between Lake Michigan and the Mississippi

was extended into the era of modern industrial shipping.

Hydrographically, we know that The Illinois River is a principal tributary of

the Mississippi River, approximately 273 miles long. The river drains a large

section of central Illinois, with a drainage basin of 28,070 square miles.

The Illinois River is formed by the confluence of the Kankakee and Des

Plaines rivers in eastern Grundy County, approximately 10 miles southwest of

Joliet – right in the backyard of Goose Lake Prairie. It flows west across

northern Illinois, passing Morris and Ottawa, where it is joined by the Mazon

River and Fox River. At LaSalle, it is joined by the Vermilion River, then flows

west past Peru, and Spring Valley. In southeastern Bureau County it turns south

at an area known as the "Great Bend," flowing southwest across western Illinois.

Geologically, we know that sediment-laden floodwaters of the Kankakee Torrent

and subsequent floods filled valleys with outwash incredibly quickly.

In the glacial drift are found deposits of sand, gravel, and clay.

As luck would have it, that

"underutilized channel" mentioned earlier means that these ancient deposits are

not swept away.

Land elevation

drops just 21 feet in the more than 200 miles from the head of the Illinois

River to where the Illinois empties into the Mississippi. The river has so

little energy that it cannot even carry away all the sediments dumped into it by

its tributaries, much less sweep the valley of sediments deposited during its

drastic glacial past.

The boundaries of prairie wetlands may change as they tend to dry out near the

soil surface during late summer because of hot temperatures and occasional

summer droughts.

The presence of

wetlands makes for high biodiversity within the prairie landscape, and creates

interesting and colorful places to visit during the growing season.

From the historical perspective we know that the prairie / wetlands interface

was common throughout our state. Consider that at least 60 percent of Illinois’

land area was once grassland of one type or another and prior to European

settlement, wetlands covered millions of acres of Illinois, or about 23 percent

of the land.

So remember on your next visit to Goose Lake Prairie that a river ran through it, but a glacier came first, and together left us “feats of clay”. Clay played a major role in the history of Goose Lake Prairie – but that’s a topic for a future story! Thanks for reading, and enjoy the prairie!

Submitted by

Chris RollinsOur special article on Illinois Prairie History this month was written by Christopher Rollins.

Chris is in his third year as Regional Land Manager, IDNR Region 2 and frequents Goose Lake Prairie SNA very often. Chris holds a double major in Animal Science; and Political Science and a Bachelor of Arts -Board of Governors’ Degree from Western Illinois University.

At first glance the fast pace of our modern daily lives circa 2009 appears to

have little in common with the lives of our forefathers here on the prairie

nearly 160 years ago.

On closer

examination there are circumstances that ring familiar and can be more fully

understood because of our recent history.

During the 12 months ended July 1, 2005, one of the top-10 fastest-growing

counties in the

Let’s step into the time machine and visit the same area circa 1850. By the time

the 1860 census was tallied,

.jpg) A Turtle With

A Yellow Chin

A Turtle With

A Yellow ChinYou may have seen numerous nets in several marshes at Goose Lake prairie and asked yourself, what are those? Well, they are turtle traps. I have been trapping turtles, specifically Blanding’s turtles for two years now. Goose Lake prairie is one of the few places left in the state where there appears to be a thriving population, although their status is unknown. I have captured 57 Blanding’s turtles in 9 weeks of trapping over 2 years. In addition, around 70 painted turtles and a handful of common snapping turtles have also visited my nets. The next several years should paint a better picture of the status of Blanding’s turtles at Goose Lake prairie.

Blanding’s turtles are a medium sized turtle, to about 10 inches long that inhabits shallow marshes with emergent vegetation, wet prairies, sloughs and bogs. A dark shell speckled with numerous yellow spots and a bright yellow chin is the distinguishing characteristic. Blanding’s turtles were once common throughout its range, which extends from Nebraska eastward to southern Ontario, with disjunct populations in New York, New England, and Nova Scotia, while the Great Lakes region is the stronghold of the species. It is listed and endangered or threatened in 10 states and 2 Canadian provinces. The major problem facing Blanding’s turtle today, particularly in Illinois, is habitat fragmentation and destruction.